The "dial-up" era of cryptocurrency

How the Internet went mainstream and what we may learn from it for the coming arc of crypto

Since I first used Bitcoin in 2013 and started paying attention to Ethereum in 2016, I’ve had little doubt that the emergence of cryptocurrency and blockchain technology was a movement as significant as the rise of the consumer-accessible Internet. What the Internet did for information, public blockchains will do for digital asset ownership and economic coordination.

We are still in the early stages of the rise of cryptocurrencies and public blockchains, but for those of us who grew up during the late 1980s / early 1990s and were heavily immersed in the Internet, the parallels are unmistakable. But many of the participants in cryptocurrency today are younger (under the age of 30) and do not have the benefit of hindsight from the rise of the consumer Internet during the 1990s. They simply don’t remember a time when the Internet was not an “always on” utility, nor how we arrived at the point where it became one.

In this post, I’ll share echoes from some of that history as someone who grew up actively using those emerging Internet technologies, draw parallels to crypto today, and offer some insight for what may come next.

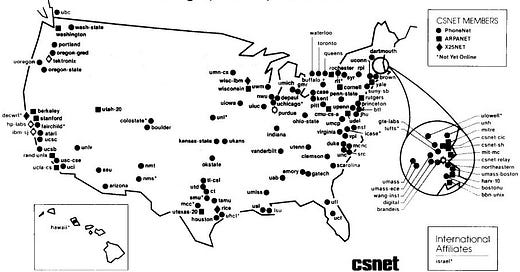

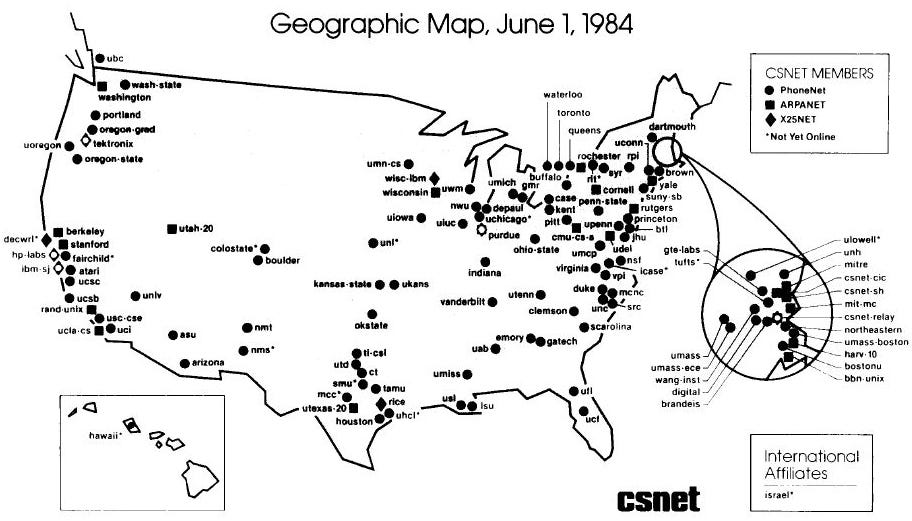

The origins of the Internet as ARPAnet

ARPAnet was created by the US Department of Defense in the late 1969 as a way to connect computers between universities. At the time, there was a desire to share information and computing power between these institutions. The intent of ARPAnet was to create a technology which the Department of Defense could eventually use to link its own mission critical systems electronically through a hardwired network. But access to this early network was controlled by the government and limited to participating institutions.

ARPAnet produced critical innovations which would eventually form the backbone of the consumer Internet, including the TCP/IP protocol (still used today as the foundation of Internet-based data exchange) and eventually led to turnover of network operation to commercial Internet providers during the 1990s.

Early adopters of Usenet and Bulletin Board Systems

Many who were alive back in the 1980s and early 1990s probably don’t remember Usenet or bulletin board systems (BBS’s), but prior to the rise of dial-up access to the Internet, these were important tools independent participants used to share knowledge and data with one another. They were primarily the purview of early adopters, but helped to pave the way to the “information age” we still find ourselves in today.

During the early 1980s, personal computers (PCs) became much cheaper, landing them in the hands of retail consumers. Soon, users could purchase modems which they could install in their PCs to access data services via their phone lines. For the first time, users were able to communicate with one another electronically and share software programs—even without access to the original physical media in the form of floppy disks.

Usenet, created in the early 1980s by researchers at the University of North Carolina and Duke, grew into a large and diverse network. At first, it gained in popularity among institutions which were not given access to ARPAnet, and grew from there to become a popular way for consumer enthusiasts to communicate with one another on all manner of topics. For a time, you could find a “newsgroup” on both popular and niche topics. Newsgroups were online forums where users could share typed articles, digital images, and participate in forum discussions. When content was posted to one server, the system propagated that content across the entire network. Usenet had started to emerge as its own form of a limited Internet for independent users; however, Usenet was fundamentally limited in what it could do with newsgroups (effectively, a single application).

Bulletin board systems (BBS’s) emerged in parallel to Usenet and were more focused on local participants (i.e., often within the same phone area code). Users would dial-in to their local BBS and could see news and updates in an ASCII text interface, share messages outside of that BBS via FidoNet, and most popularly, download software. BBS’s would become a primary distribution mechanism for shareware/freeware software and frequently contain illegally distributed commercial software known as “warez.” Capacity and bandwidth over phone lines was limited, and downloads could take hours; and if anyone in your house picked up the phone while you were downloading, you’d likely lose your connection have to start over at the beginning. It was hard to use, but incredibly powerful. But with operators in almost every population center in the US, BBS’s illustrated the possibilities of what online information sharing and interaction could look like.

The dial-up era of the Internet and how it went mainstream

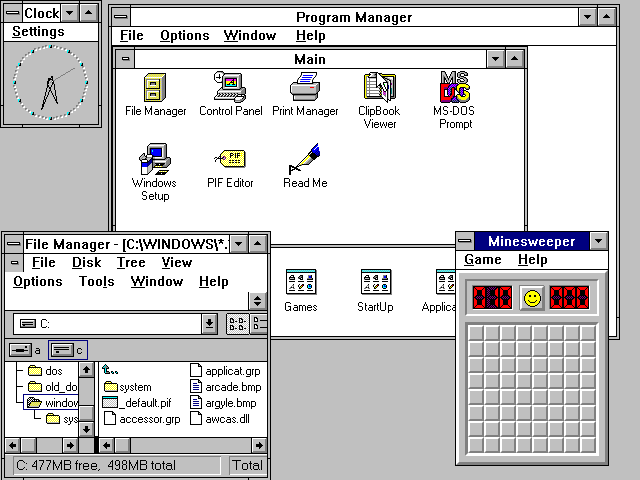

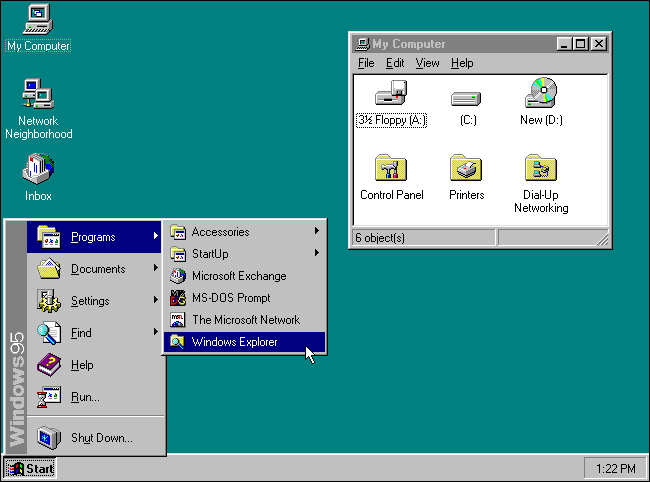

Enter the 1990s, when everything changed: Many first used computers at work for word processing and other productivity purposes, and many saw value in eventually purchasing such devices for their homes. They became far easier to use with the rise of refined graphical interfaces with the launch of Windows 3.0 in 1990. This quickly advanced to more refined user interfaces such as Windows 95, released in 1995- an interface very similar to the one many PC users use today almost 30 years later. They played a growing library of computer games on them (normalized through the rise of at-home gaming consoles during the 1990s). And importantly many of those computers came preinstalled with a modem allowing them to connect to data services over their telephone lines.

The environment was primed to get these users online, but to be successful, they’d need a polished experience—devoid of the hassles faced by early Usenet and BBS participants. No confusing interfaces. Just a focused online experience allowing people to do things they had never done before. Commercial Internet Service Providers (ISPs) emerged to answer the call.

Consumer-oriented ISPs quickly gained popularity as people learned their computers could connect to these services. Most started by charging customers quite high rates for access by the hour (as high as ~$10 per hour), plus any additional phone line fees. But over time as the technology scaled, ISPs were able to drop rates to as low as $20 per month for unlimited access.

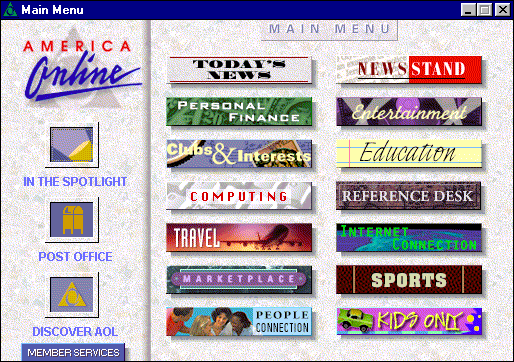

America Online (AOL) was the most famous of these dial-up Internet access services, alongside Prodigy, CompuServe, and others. The iconic refrain of “You’ve Got Mail!” upon signing-on was a point of excitement for new users. For the first time, people discovered e-mail, one of the most basic Internet applications. They started communicating with friends and relatives electronically. No longer did you need a long distance phone call to catch up with someone far away, or write a paper letter- you could just draft an e-mail and send it. The recipient would get it almost instantly. “Instant Messenger” allowed users to chat with one another in real time, allowing entire text-based conversations. Live chat rooms emerged where people could discuss almost any topic, and users could participate in niche communities focused on their respective interests—even if they did not know a single person in their “real” lives who shared those interests.

It’s difficult to overstate how magical all of this felt for new participants. Of course, a lot of these things could have been done without AOL through the direct POP/SMTP e-mail protocol, Usenet groups, IRC chat rooms, etc. But what AOL did was make it all extremely easy to use and accessible at scale. This was a game changer.

AOL also took what was a hard to parse lump of information on the Internet and carefully curated it. Remember, this was before the days of effective search engines like Google, and finding things on the Internet was difficult. Understanding which sites were reputable or not took time for new users. AOL stripped away this complexity and simply delivered information organized around key topics their customers were interested in, and many early users of AOL never ventured beyond these walls.

But importantly, AOL eventually allowed access to the free and open Internet for users, and over time, pressure mounted for them to expand and improve that access. This included allowing users to eventually access Usenet (which by now had migrated to the Internet’s TCP/IP-based infrastructure), support user-defined browsers for use on the World Wide Web like Netscape (versus just the limited AOL-built-in browser), etc.

In many important ways, AOL and others provided necessary training wheels to help get people on the Internet; and those training wheels were critical to driving mainstream adoption. But once people got comfortable with using these services, they eventually did not see much use for the curated content and relatively closed ecosystem AOL provided; and many certainly did not feel that they needed to pay a premium to gain access to them.

At that point, more pure play ISPs started to gain in popularity. These services provided “no frills” access to the Internet. You got several dial-in numbers (in case some were busy during peak hours), an e-mail address, and that’s it. But from there, using Netscape or Internet Explorer, the two most popular browsers of their day, you could access the entire Internet. Users had finally adjusted from wanting a training wheels experience, to preferring one which gave them the value they ultimately desired: free and open access to the open Internet and nothing else.

Modem technology also continually improved during the 1990s, allowing users to benefit from higher speed connections over their existing phone lines. At first, many customers first connected to the Internet at slow speeds of less than 14.4 Kbps (kilobits per second) in 1991, eventually rising to 56 Kbps by 1998- an almost 4x speed improvement, made even more meaningful by improving compression technology over that same time period.

It was not until the early 2000s that DSL and cable modems took off as a popular “broadband” connection options for retail users, representing a quantum leap in speed for home users. Cable Internet ultimately became the most popular and allowed home users to reach download speeds of up 25 Mbps (megabits per second) or more—a ~215x speed increase. Today, it is not uncommon to find Internet connection speeds of up to 400 Mbps—or nearly 3500x the speed of a 14.4 Kbps modem!

To put this in perspective, if you were to hypothetically download a popular game (now often ~30 gigabytes in size), it would take you less than an hour on most cable Internet connections. If you were to try and download the same game on a 14.4Kbps Internet connection, it would take you in excess of 4900 hours—or over 200 days! This increase bandwidth was essential to bringing us the dynamic and media-rich “web 2.0” experience we are used to today. Without that dramatic increase in bandwidth, the Internet as we know it today would likely be very different.

Cable Internet connections also helped popularize the notion of the Internet as an “always-on” utility which users no longer had to “dial-in and log-on” to. With the advent of the iPhone in 2007, consumer use of the Internet on their phones became far more popular. Now, there is practically no barrier between you and the Internet. And if you grew up with it, you probably consider it akin to a utility service like water, gas or electricity.

Takeaways from the dial-up era of the Internet

Getting people to understand the value proposition of the early Internet and glean real value from using it was essential to its adoption (e.g., e-mail, forums, chat), and this value increased with the number of participants

On-boarding had to be made simple enough so that almost anyone could participate (e.g., the AOL-effect)

The push towards ever-improving connection speeds was needed to continually realize new potential from the Internet

Lessons for the current “dial-up” era of crypto

In many ways, I feel that we are in the dial-up era of crypto—especially when it comes to actually using chains which employ smart contract logic like Ethereum; not just speculating on their tokens.

As it was for participants in the Internet during the early 1990s, we are at a stage where it is obvious to us early adopters that crypto will be transformative. We know that it is very hard to use today, but we know it will get easier. We know that it will eventually transform commerce and society, but we do not know exactly what these changes will look like. And we know there will be booms and busts, but with each cycle, we iterate with the introduction of game-changing functionality.

In the past several years, crypto has made massive strides towards becoming accessible to more mainstream users—moving beyond a niche technology to one where many can participate. For those of us in the trenches it may not seem like it, but these shifts in usability (and thus, adoption) have been staggering. Some selected milestones include:

2009 - Bitcoin launches

2010 - Mt Gox exchange goes online and becomes a prominent Bitcoin exchange

2011 - BitPay was founded to facilitate payments via Bitcoin

2012 - Coinbase launches as the first consumer-friendly crypto exchange in the US

2014 - Trezor releases the first consumer-friendly hardware wallet

2015 - Ethereum launches

2015 - The Mist browser launches to interact with Ethereum / Web3

2016 - MetaMask browser extension launches to interact with Ethereum / Web3

2018 - Robinhood adds crypto listings (custodial)

2018 - MetaMask browser extension integrates hardware wallet support

2020 - Argent launches non-custodial smart contract wallet

2020 - Matic Network (now Polygon) launches as an Ethereum Virtual Machine-compatible side chain

2020 - High-throughput, non-EVM blockchains such as Solana launch and attract many lower cost use cases

2021 - NFTs enter the zeitgeist and become a significant driver for new crypto participants

2020-2022 - Multiple Ethereum zk-rollup and optmistic rollup L2s begin to launch in various states of functionality

While crypto user experience (UX) has come a long way in its relatively short history, there is no doubt we are still very early in this journey. Most users still participate in curated or custodial experiences. L2s will add significant transaction capacity to the Ethereum ecosystem and will allow for the exploration of new use cases, just like the addition of more bandwidth to Internet connections did during the dial-up and post-dial-up era. Similarly, other blockchain networks will make different kinds of tradeoffs and the market will decide which approaches add the most value to this still nascent space.

It’s an exciting time to be here. Things will get easier, but also crazier. And crypto’s “Eternal September” moment may finally be here thanks to NFTs, but that’s a post for another time…